Victoria Gold, The Little Company That Could

Victoria Gold’s Eagle Gold Mine is ramping up to produce a quarter of a million ounces yearly.

By Robert Simpson

A long history of gold exploration

In 2020, on Canada Day, despite skeptics who said the regulatory hurdles were insurmountable, gaining local and Indigenous support unattainable, and single asset companies can’t raise the money needed for mine construction, Toronto-based Victoria Gold (TSX: VGCX) joined the ranks of Canadian gold producers at its Eagle Gold Mine.

Conventional business models in the mining industry are for mineral exploration companies to define the ore deposit and sell the property to a larger mining company to bring it into production. But like in the fable The Engine That Thought It Could, after all the large locomotives refused to pull the train over the mountain, the small engine succeeded by repeating, “I-think-I-can.” Victoria developed the Eagle Gold Mine from start to finish.

After investing almost $150 million in environmental assessment studies, feasibility studies and permitting, construction of the Eagle Gold mine kicked off in August of 2017.

Another $487.2 million was injected into the Yukon economy and businesses through contracting and mine services for the mine construction costs.

Today, the Eagle Gold Mine is the largest non-public sector employer in Yukon, with 500 employees and contractors, contributing almost 10 percent of the Territory’s annual GDP.

“Victoria Gold is unique. Not many companies take projects from exploration to operation,” says John McConnell, president and CEO of Victoria Gold.

The company’s achievement of ‘chip sample to gold pour’ hasn’t gone unnoticed. Last year, McConnell and the Victoria Gold team were recognized with the Association of Mineral Exploration BC’s EA Scholtz Award for Excellence in Mine Development.

The team was recognized for developing and financing the mine as a single asset company and building and operating a mine in the North, changing the way people can and should think about mine development in northern regions.

Victoria’s flagship Eagle gold mine is situated on the Dublin Gulch gold property in the central Yukon Territory, about 375 kilometres north of Whitehorse and approximately 85 kilometres from the town of Mayo, and over the years, the region has seen significant exploration.

According to “Dublin Gulch: A History of the Eagle Gold Mine,” by Michael Gates, the earliest staking in the Dublin Gulch area was reported to have occurred in 1897 at the head of Johnston Creek, and the first recorded gold discovery a year later in 1898 ahead of the Yukon Gold Rush.

Interest in the Dublin Gulch area waned over the years. It didn’t heat up again until almost seventy years later when the Fort Knox deposit near Fairbanks, Alaska, was discovered, and geologists recognized similarities in the intrusion-related gold systems.

In 1994, First Dynasty Mines Ltd acquired Ivanhoe Goldfields Ltd. Its wholly owned subsidiary, New Millennium Mining, carried out a significant drilling program to outline a core resource in the Eagle Zone.

First Dynasty put the project on hold when the gold price dropped to below US$250 in 1997, and it sat idle until 2004, when Stratagold acquired the property.

Stratagold drilled 34 diamond drill holes (8,105 metres) in 2005 targeting the Eagle zone, step-out from the Eagle Zone along strike and metasedimentary rocks surrounding the mineralized pluton.

In 2006, 4,280 metres of diamond drilling in seven widely spaced holes were completed, along with extensive soil sampling and trenching.

Twenty diamond drill holes, for a total of 5,528 metres, were completed at Dublin Gulch in 2007. In 2008, another 15 holes (4,248.7 metres) were drilled in the Eagle zone.

At the same time, Stratagold consolidated the Dublin Gulch property into a contiguous block that extends 26 kilometres in an east-west direction and 13 kilometers in a north-south direction, an area of approximately 555 square kilometers.

Stratagold also started down the road of permitting the Eagle deposit, but by 2009 the company treasury had run dry, and Victoria Gold picked up the property for a $10 million share swap, which translated into about C$3.00 per ounce of gold.

“After we confirmed the Eagle deposit had similarities to Ft. Knox, we finally reached an agreement with Stratagold when they couldn’t make the payroll,” says McConnell.

Over the next decade, Victoria Gold methodically advanced the Eagle Gold Mine, beginning with in-fill drilling at the Eagle and Olive deposits to shore up the gold reserves.

A 2019 feasibility study reported proven and probable reserves of 3.3 million ounces of gold from 155 million tonnes of ore with a grade of 0.65 grams per tonne.

The Eagle and Olive deposits are estimated to host 227 million tonnes averaging 0.67 grams of gold per tonne, containing 4.7 million ounces of gold in the measured and indicated category, including proven and probable reserves.

A further 28 million tonnes averaging 0.65 grams of gold per tonne, containing 0.6 million ounces of gold, were reported in the inferred category.

In December 2010, Victoria Gold submitted a project proposal, initiating the environmental assessment process.

Over the next three years, Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Board reviewed the application. In April 2013, the Yukon Government Department of Energy, Mines and Resources issued a Quartz Mining License for the Eagle Gold Project.

“The environmental assessment process took longer than expected, but we benefited from having a Comprehensive Cooperation and Benefits Agreement with the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun,” says McConnell.

The Cooperation and Benefits Agreement provides business and employment opportunities, environmental stewardship, transparent communication and dispute resolution mechanisms.

“People always say you’ve got a good relationship with the local community and the Na-Cho Nyäk Dun, and that’s because we continuously work at it. A relationship is a lot more than signing an agreement. It’s a partnership, and with any partnership, it takes hard work and maintenance on both sides to make it work,” says McConnell.

“It took years of careful consultation and negotiation to establish a solid social license between our two parties. We worked with Victoria for many years establishing a mutually beneficial relationship, to the point where Victoria Gold now exemplifies the model for companies wishing to work in our traditional Territory,” says Simon Mervyn, Chief of the Na-Cho Nyäk Dun First Nation.

Optimizing gold production during a pandemic

Fast forward to 2022, and based on current reserves, the Eagle deposit will provide 110.4 million tonnes of ore, while the Olive deposit will provide 6.5 million tonnes for a total of 116.9 million tonnes from January 2020 until the completion of operations in 2030.

Fast forward to 2022, and based on current reserves, the Eagle deposit will provide 110.4 million tonnes of ore, while the Olive deposit will provide 6.5 million tonnes for a total of 116.9 million tonnes from January 2020 until the completion of operations in 2030.

An additional 32.1 million tonnes of low-grade ore will also be mined over this period, resulting in a total extraction of 149.0 million tonnes. Waste mining will total 144.9 million tonnes for an overall strip ratio of 0.97:1.

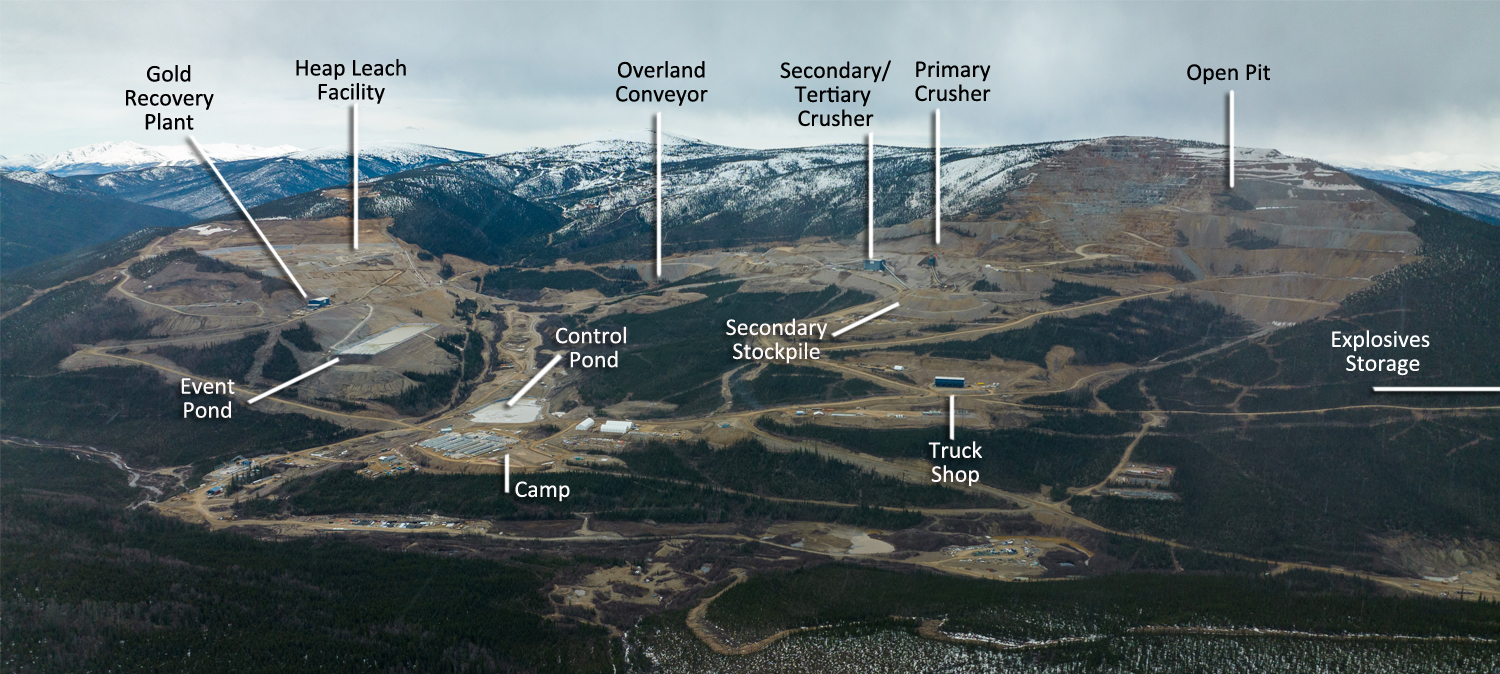

Gold is extracted from ore into a solution by a heap leaching process using two heap leaching pads, a primary and a secondary.

Heap leach feed consists of crushed ore conveyed to the pads and run-of-mine un-crushed ore, which is hauled directly to the pads for leaching.

Gold is leached with cyanide solution and recovered by an adsorption-desorption-recovery carbon plant. A total of 2,406 million ounces of gold will be recovered over a thirteen-year mine life from 77% overall recovery.

Since the start of production, the Eagle Gold Mine has produced 354,493 ounces of gold, generating a pre-tax revenue of $668 million. The company is on track to produce 165,000 to 190,000 ounces of gold in 2022 and aims to ramp up production to 250,000 ounces of gold annually by 2025.

“During the first few years, we didn’t stack ore on the leach pad during the coldest months of the year. But we keep shortening that non-stacking time, and now that we’ve got three winters under our belt, we’ve reduced the six-week winter maintenance shutdown, which will significantly improve gold production,” says McConnell.

“During the first few years, we didn’t stack ore on the leach pad during the coldest months of the year. But we keep shortening that non-stacking time, and now that we’ve got three winters under our belt, we’ve reduced the six-week winter maintenance shutdown, which will significantly improve gold production,” says McConnell.

During the best of times, optimizing production has its challenges but ramping up during a pandemic comes with its own unique set of issues. For example, Yukon’s mandatory quarantine, which was in effect until late 2021, prevented Victoria Gold from having suppliers at site to fine-tune equipment and processes.

Supply chain disruptions have exacerbated the maintenance difficulties as certain parts have taken longer to secure and deliver to site,” the company said in its Q2 Financial News release.

With Covid restrictions now lifted, the company plans for mine optimization include adjusting the crushing and conveying system to reduce the downtime, implementing a fleet management system, and optimizing blasting performance.

“Yukoners coming back home to work at the mine is one of the things I’m most proud of,” says John McConnell, president and CEO of Victoria Gold.

New infrastructure initiatives include expanding the heap leach pad, a new truck shop and a new water treatment facility.

“It appears the production issues continue to improve, and we would suggest that Eagle can build momentum as Victoria Gold continues to ramp up production,” says Andrew Mikitchook, precious metals and minerals analyst at BMO Capital Markets.

Inflation and labour markets present unique challenges

“I’d say the biggest challenge we have working against us now is inflation and labour recruitment and retention. Rising costs for labour, energy and equipment and continued supply chain constraints have created a snowball effect increasing operating costs,” says McConnell.

According to Statistics Canada, job vacancy rates in mining last year reached a record high of 4.3%, representing more than 8,600 open positions.

“One of our advantages when it comes to attracting labour is that we focus our recruitment on Yukoners. Historically, Yukon has a rich mining industry, and there are many good people, so it only makes sense from a logistics perspective and a cost perspective to focus on Yukon. We’ve had great success, and almost 50 percent of our workforce is local,” says McConnell.

Victoria’s recruiting effort included a successful nationwide public relations campaign; It’s Time to Come Home.

“Having Yukoners come home and work at the mine is one of the things I’m most proud of. One day I was in the dining room at the mine, and a fellow introduced himself to me and thanked me for the job and for bringing him back home to his community where his eight-year-old daughter was getting to know her family. Another told me a year ago he was living under an overpass in Vancouver, and now he was living in his own house Mayo. These are the stories I love,” says McConnell.

Regional exploration potential

With 555 square kilometres of property, Victoria Gold’s exploration evaluates multiple satellite deposits with mineralization potential above the current reserves estimates.

Beginning with the Raven Gold Deposit, located approximately 15 kilometres east of the Eagle Gold Mine.

A recent mineral resource estimate representing the culmination of diamond drilling and surface exploration programs conducted through 2021 resulted in an initial assessment comprising a total Inferred Mineral Resource of 1,070,239 ounces of gold.