The Past and Future Legacy of Windy Craggy

The 1993 cancelling of British Columbia’s US$31 Billion Windy Craggy Project actually benefitted other mining projects while some stakeholders were left out. Maybe it’s time to have another look at the huge cobalt, copper, zinc, gold and silver project utilizing new environmental stewardship technologies.

By Bruce Downing and Rick Van Nieuwenhuyse

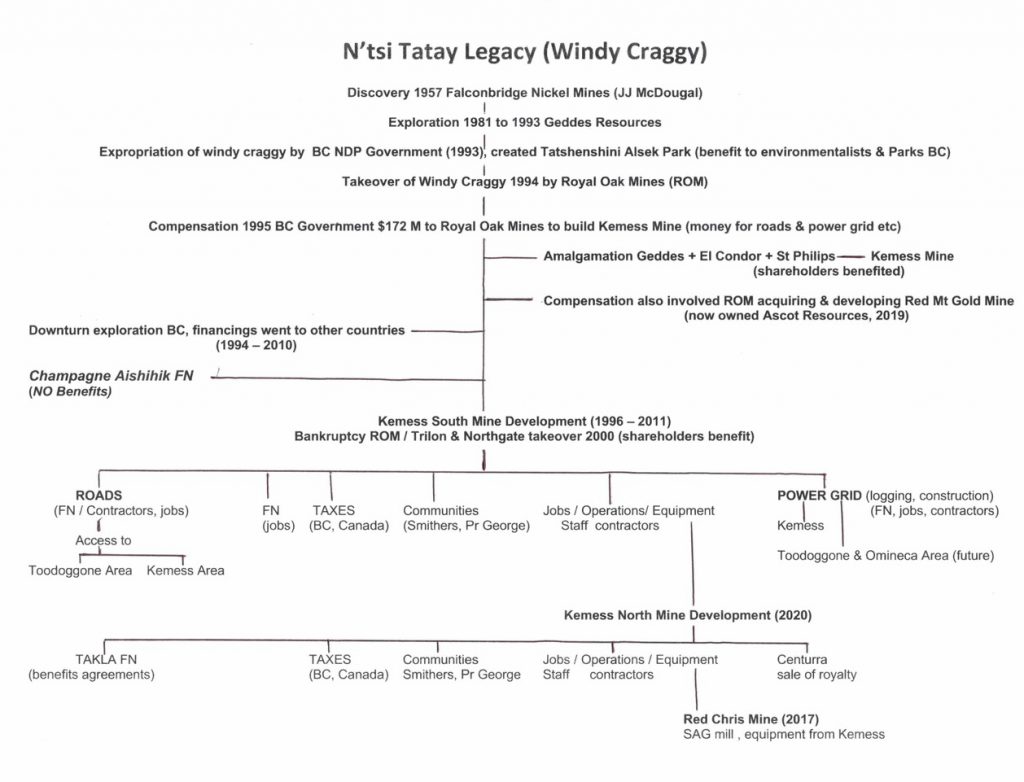

The demise of the Windy Craggy (N’tsi Tatay) Project in far northwestern British Columbia has led to numerous benefits worth more than $1,000,000,000 and enjoyed by many. This is illustrated in the accompanying Legacy Flow Chart.

In 1994 Royal Oak Mines acquired the Windy Craggy deposit and mineral claims from Geddes Resources. Work between 1988 and 1991 included 4,139 metres of underground development and 64,618 metres of drilling in 55 surface and 147 underground diamond drill holes. Two large massive sulfide zones, termed the North sulfide body (NSB) and South sulfide body (SSB), were outlined and likely a third zone (Ridge Zone) was intersected by drilling.

The 1992 non-NI 43-101 compliant historical resource estimate is 297,400,000 tonnes: 1.38% Cu, 0.069% Co, 0.20 g/t Au, 3.83 g/t Ag using a 0.5% copper cut-off grade (Geddes Resources Ltd., 1991). The deposit is likely much larger than this as the limits of the NSB, SSB, and particularly the Ridge zone have not been delineated. The NSB alone (to December 1991) contains 138.3 million tonnes in all categories grading 1.44% copper, 0.22 g/t gold, 4.0 g/t silver, 0.066% cobalt, and 0.25% zinc.

The NDP Government of British Columbia facilitated the development of the Kemess South copper-gold deposit by Royal Oak Mines as “compensation” for the 1993 appropriation of its Windy Craggy mineral properties, which became part of the Tatshenshini-Alsek Provincial Park.

Compensation, which was specifically used for power and road development to the northern interior Kemess Mine site, amounted to $160 million plus $12 million for education and training. With the development of the Kemess North Underground Mine, the Takla First Nation is now in a position to receive their due benefits some 22 years after the development of the Kemess South copper-gold mine (1998).

Many BC First Nations people have benefited from the demise of Windy Craggy while the Champaign Aishihik First Nation (CAFN) received nothing, according to former CAFN Chief James Allen. “New government-to-government and mineral tax revenue-sharing agreements provide for economic benefits and collaboration opportunities for First Nations in northern B.C. related to the proposed Kemess underground mine. Tsay Keh Dene Nation, Takla Lake First Nation and Kwadacha Nation (Kaska), collectively known as Tse Keh Nay, and the Province have signed respective Economic and Community Development Agreements.”

The legacy of Windy Craggy continues and has been the compensation (public tax money) which provided for the direct infrastructure (power and roads) base for resource development in the north-central region of British Columbia. This includes the following;

- Kemess South Mine

- Kemess North Mine

- Exploration access to the Omineca and Toodoggone copper-gold district; Omineca Mine Road; Omineca Resource Access Road (ORAR) – called Cheni Road.

- Power line built 1996, clear cutting, 70 metres wide by 320 km long, 1,800 people for 18 months, McLeod, Ingenika and Saka-Dene First Nations from the Kennedy substation, near Mackenzie

- Potential infrastructure for mine development in the Toodoggone Mine Camp

- Toodoggone area – Benchmark Metals Inc. [BNCH-TSXV; BNCHF-OTCQX; A2ATHU-FSE] (Lawyers Project) signed with Tahltan First Nation and Takla First Nation.

- A Kemess SAG mill and equipment went to the Imperial Metals Corp. [III-TSX; IPMLF-OTC] Red Chris Mine, so Red Chris benefited indirectly from Windy Craggy. Imperial Metals has signed a benefits agreement with the Tahltan.

- Because of Kemess, Canada’s Centerra Gold Inc. [CG-TSX] is selling its subsidiary AuRico Metals’Â royalty portfolio and a silver stream on its Kemess Project to Triple Flag Mining Finance Bermuda, in a deal valued at $200 million. In the case of its Kemess property in northern BC, Centerra is selling 100% of the project’s silver production for $45 million, payable in four tranches.

The legacy also provided a large park (Tatshenshini Alsek) encompassing nearly a million hectares (9,580 km2Â or 3,700 square miles) to Parks BC which benefited environmentalists, hikers, campers, tourists and governmental organizations.

The Windy Craggy compensation package committed Royal Oak Mines to develop a second mine which resulted in the acquisition of Red Mountain Gold Mines, near Stewart, BC. In 1996, Royal Oak explored for additional reserves. The company extended underground drifting by 304 metres and completed 26,966 metres of surface and underground drilling. In 2000, North American Metals Corp. purchased the property and project assets from Price Waterhouse Coopers from the bankruptcy of Royal Oak Mines and conducted detailed re-logging of existing drill core and constructed a geological model for resource estimation purposes and exploration modeling. This property was subsequently acquired by Ascot Resources Ltd. [AOT-TSX; AOTVF-OTCQX] in 2019.

The demise of Windy Craggy also resulted in mineral exploration and development funds not being invested in BC for several years, and others in BC’s resource sector saw the provincial NDP Government as generally anti-mining. Consequently, money raised during this time went primarily for exploration and mine development in numerous other countries which greatly benefited them. This mining downturn in BC resulted in loss of millions of dollars in lost revenue for BC.

Taxation and employment from the Kemess South Mine and now the Kemess North Mine developments have benefited the Governments of British Columbia and Canada and probably will be in excess of several billion dollars. Governments also benefited from road and power developments. The BC NDP government of 1993 made money from the demise of Windy Craggy from taxation dollars and an initial royalty of 4.8 % based on copper production.

A future legacy of Windy Craggy will be the North American resource and supply of copper and cobalt needed for electric vehicles and batteries. It is hard to imagine that we should not consider the project as an ethical and critical source of cobalt to be used to create a non-carbon and cleaner future.

Cobalt was a critical metal and is now considered essential. Included in this future legacy are numerous direct and indirect economic, employment, societal (health care dollars), community, parks, fishery and First Nation benefits.

Recent innovations in recovery technology, mine development, block caving, cemented back fill paste and dry stack tailings storage techniques, along with world environmental management and mitigation strategies offer opportunities for the sustainable and environmentally responsible development of the Windy Craggy deposit in ways which were not envisioned when the deposit was put into the park. Other such new and innovative technologies would include onsite power via runoff river hydro and wind power as well as full reclamation plan and design of facilities for present and future use (ie post-mining).

This new technology is needed in order to build a mine utilizing Indigenous knowledge and good environmental stewardship that will adhere to climate change policies, fishery management to develop a domestic North American supply chain of cobalt which will help to eliminate the present child labour, corruption, crime, poverty, hazardous artisanal mining scenarios in the Congo. This development would have a lasting impact on the Covid-19 economy recovery.

The Windy Craggy story begs two questions:

How many undeveloped deposits have contributed so much to society in terms of wealth creation without having been mined? Answer: None. Windy Craggy is unique in this category.

What was the RISK associated with the demise of Windy Craggy?

Answer: The Kemess South Mine would not have been developed had it not been for the risk taking in 1994 of Margaret (Peggy) Kent, CEO of Royal Oak Mines. She and her colleague Ross Burns saw an opportunity for development in BC with the demise of Windy Craggy. They purchased the Windy Craggy property from Northgate and then sought compensation from the BC NDP government. The compensation package received for Windy Craggy facilitated the acquisition and development of the Kemess South Property and acquire and the development of the Red Mountain Mine Property.

Unfortunately, the government compensation package did not include the CAFN who were left to their own devices regarding their land claim status and resource development.

In our opinion, we need to create wealth by investing in Windy Craggy for the benefit of future generations. Windy Craggy can become part of the solution for the battery resource of cobalt and copper for the electric vehicle. The BC and Federal governments can become part of the solution for the quest of cobalt (and copper) for the development of clean technology in electrified vehicles.

Bruce W. Downing, MSc., PGeo, FGC, FEC(hon) is a consultant who has been involved with Windy Craggy since 1975 to present and was Project Geologist from 1989 to 1991.

Rick Van Nieuwenhuyse, MSc., is mining executive who founded Novagold Resources and Trilogy Metals. He is currently President and CEO of Contango Ore Inc. and working with the Tetlin Alaska Native Tribe to develop the Peak Gold deposit in Alaska.