The Dawn of an Iron Ore Super Cycle

By Sandy Chim, Chairman, President, CEO

Century Global Commodities Corp.

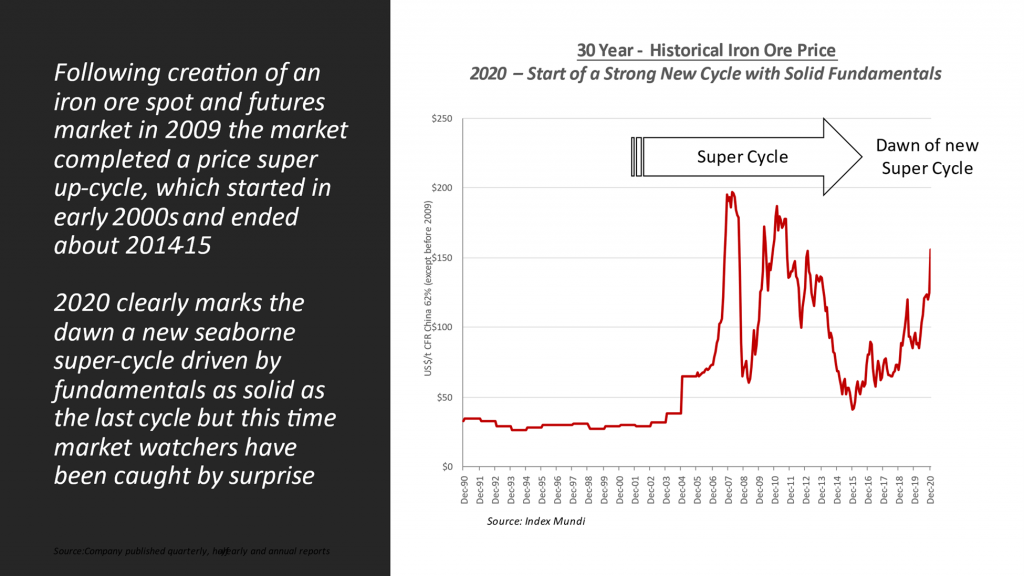

The end of the last iron ore Super Cycle in early 2014 hit hard especially when the price bottomed in late 2015 at less than US$40/t. The pull-back depth and six-year span left forecasters with protracted pessimism coupled with depressing price outlooks and a view that seaborne market recovery, flooded by new mine projects was unimaginable.

The view was entrenched, even when iron ore price topped US$120/t in mid-2019 and was interpreted simply as a one-time impact after Vale’s tragic tailings dam failure from earlier that year. The entrenched pessimism was so tenacious it blinded observation of steadily improving fundamentals and development of a strong healthy market.

To the surprise of all market watchers, iron ore price increased by 74% in 2020, remarkably outperforming all other metals by a significant margin. As a result of iron ore’s upward price trajectory over the last two years, industrial and financing market players are being convinced of the demonstrated sustainable recovery so much so that the dawn of a new iron ore Super Cycle is becoming a reality. Iron ore reached close to US$180/t (62% Fe, CFR China) in December 2020, a level not been seen for almost ten years and in 2021 through late January it has continued in the range of US$170/t. The potential of a new Super Cycle is brought into greater focus when quantitative easing coupled with massive fiscal stimuli are expected to be the key tools for global economic recovery, in a post-COVID-19 world.

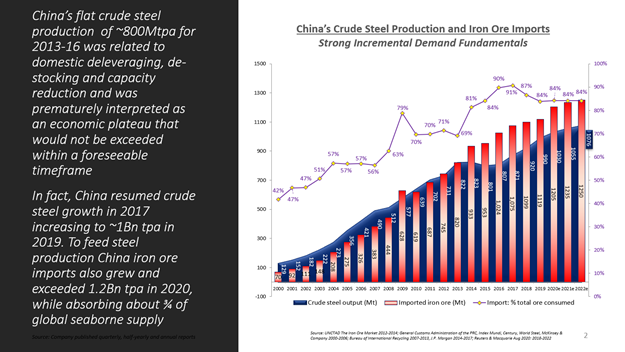

Pessimism at the bottom of the cycle was not baseless in the context of demand. Protracted future low iron ore prices were predicted starting in 2013 when demand from China (which produces about half the world’s steel and consumes three-quarters of global seaborne iron ore supply) appeared to plateau at a steel peak output of about 800M tpa and also at a time when mainland China super-infrastructure projects were reaching completion and its run-away property market bubble defused.

That “peak” plateau of steel output persisted for 3-4 years (2013-2016) and coincided with China’s efforts at deleveraging excessive debt, de-stocking inventories and reducing capacity. With fiscal house cleaning complete, China resumed incremental growth and by 2020 crude steel production exceeded 1Bn tpa, an increase of 200M tpa over the prior plateau peak! This healthy growth worked its way into the iron ore market and by 2020 provides the environment for a recovery and dawn of a new super cycle, an opportunity unimaginable by many just a few years previous. In fact, while steel output levelled during the peak, import of iron ore never stopped growing.

On the global seaborne supply side, pressure opposing a return of a bull market was even greater. When Fortescue came into the iron ore market in the mid-2000s armed with a disruptive plan to contribute ~200M tpa to the seaborne market, when the Big 3 contributed only a total of ~500M tpa. To maintain market share and to address burgeoning China demand the oligopoly, which in a few years grew to four players, embarked on massive expansions with about US$100B invested in the expansion process while maintaining about 70% share of the seaborne market.

Over just a few years, the Big 4 doubled iron ore production to over 1Bn tpa while reducing FOB C1 cash cost to about US$15/t, seriously limiting potential new market entrants. They set the curve cost so low that spot prices were not expected to return anywhere near the peak of the last Super Cycle and the situation entrenched a pessimistic outlook of a protracted bottom and long road to recovery. However, the Big 4 have not committed new major expansion capital (other than sustaining capital) since from before 2015 and this has terminated new supply while China demand has continued to grow.

The gradual and incremental Chinese iron ore demand growth against the lack of mine expansions by the oligopoly has capped seaborne mine supply creating a new market structural reality underpinning the solid recovery we see today. This structure will not change until another round of major mine expansions, which takes five to ten years to reach production after capital commitment – the conditions necessary to usher in a new Super Cycle.